Last summer, after months of encrypted emails, I spent three days in Moscow hanging out with Edward Snowden for a Wired cover story. Over pepperoni pizza, he told me that what finally drove him to leave his country and become a whistleblower was his conviction that the National Security Agency was conducting illegal surveillance on every American. Thursday, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York agreed with him.

In a long-awaited opinion, the three-judge panel ruled that the NSA program that secretly intercepts the telephone metadata of every American — who calls whom and when — was illegal. As a plaintiff with Christopher Hitchens and several others in the original ACLU lawsuit against the NSA, dismissed by another appeals court on a technicality, I had a great deal of personal satisfaction.

It’s now up to Congress to vote on whether or not to modify the law and continue the program, or let it die once and for all. Lawmakers must vote on this matter by June 1, when they need to reauthorize the Patriot Act.

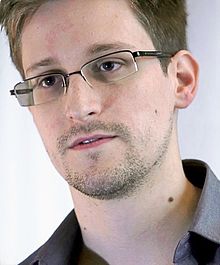

Edward Snowden during an interview with Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, June 6, 2013. WIKIPEDIA/Screenshot of a Laura Poitras film by Praxis Films

A key factor in that decision is the American public’s attitude toward surveillance. Snowden’s revelations have clearly made a change in that attitude. In a PEW 2006 survey, for example, after the New York Times’ James Risen and Eric Lichtblau revealed the agency’s warrantless eavesdropping activities, 51 percent of the public still viewed the NSA’s surveillance programs as acceptable, while 47 percent found them unacceptable.

After Snowden’s revelations, those numbers reversed. A PEW survey in March revealed that 52 percent of the public is now concerned about government surveillance, while 46 percent is not.

Given the vast amount of revelations about NSA abuses, it is somewhat surprising that just slightly more than a majority of Americans seem concerned about government surveillance. Which leads to the question of why? Is there any kind of revelation that might push the poll numbers heavily against the NSA’s spying programs? Has security fully trumped privacy as far as the American public is concerned? Or is there some program that would spark genuine public outrage?

Few people, for example, are aware that a NSA program known as TREASUREMAP is being developed to continuously map every Internet connection — cellphones, laptops, tablets — of everyone on the planet, including Americans.

“Map the entire Internet,” says the top secret NSA slide. “Any device, anywhere, all the time.” It adds that the program will allow “Computer Attack/Exploit Planning” as well as “Network Reconnaissance.”

One reason for the public’s lukewarm concern is what might be called NSA fatigue. There is now a sort of acceptance of highly intrusive surveillance as the new normal, the result of a bombardment of news stories on the topic.

I asked Snowden about this. “It does become the problem of one death is a tragedy and a million is a statistic,” he replied, “where today we have the violation of one person’s rights is a tragedy and the violation of a million is a statistic. The NSA is violating the rights of every American citizen every day on a comprehensive and ongoing basis. And that can numb us. That can leave us feeling disempowered, disenfranchised.”

An illustration picture shows the logos of Google and Yahoo connected with LAN cables in a Berlin office, October 31, 2013. REUTERS/Pawel Kopczynski

In the same way, at the start of a war, the numbers of Americans killed are front-page stories, no matter how small. But two years into the conflict, the numbers, even if far greater, are usually buried deep inside a paper or far down a news site’s home page.

In addition, stories about NSA surveillance face the added burden of being technically complex, involving eye-glazing descriptions of sophisticated interception techniques and analytical capabilities. Though they may affect virtually every American, such as the telephone metadata program, because of the enormous secrecy involved, it is difficult to identify specific victims.

The way the surveillance story appeared also decreased its potential impact. Those given custody of the documents decided to spread the wealth for a more democratic assessment of the revelations. They distributed them through a wide variety of media — from start-up Web publications to leading foreign newspapers.

One document from the NSA director, for example, indicates that the agency was spying on visits to porn sites by people, making no distinction between foreigners and “U.S. persons,” U.S. citizens or permanent residents. He then recommended using that information to secretly discredit them, whom he labeled as “radicalizers.” But because this was revealed by The Huffington Post, an online publication viewed as progressive, and was never reported by mainstream papers such as the New York Times or the Washington Post, the revelation never received the attention it deserved.

Another major revelation, a top-secret NSA map showing that the agency had planted malware — computer viruses — in more than 50,000 locations around the world, including many friendly countries such as Brazil, was reported in a relatively small Dutch newspaper, NRC Handelsblad, and likely never seen by much of the American public.

A parabolic reflector with a diameter of 18.3 metres (60 ft.) at the National Security Agency’s former monitoring base in Bad Aibling, south of Munich, June 6, 2014. REUTERS/Michaela Rehle

Thus, despite the volume of revelations, much of the public remains largely unaware of the true extent of the NSA’s vast, highly aggressive and legally questionable surveillance activities. With only a slim majority of Americans expressing concern, the chances of truly reforming the system become greatly decreased.

While the metadata program has become widely known because of the numerous court cases and litigation surrounding it, there are other NSA surveillance programs that may have far greater impact on Americans, but have attracted far less public attention.

In my interview with Snowden, for example, he said one of his most shocking discoveries was the NSA’s policy of secretly and routinely passing to Israel’s Unit 8200 — that country’s NSA — and possibly other countries not just metadata but the actual contents of emails involving Americans. This even included the names of U.S. citizens, some of whom were likely Palestinian-Americans communicating with relatives in Israel and Palestine.

An illustration of the dangers posed by such an operation comes from the sudden resignation last year of 43 veterans of Unit 8200, many of whom are still serving in the military reserves. The veterans accused the organization of using intercepted communication against innocent Palestinians for “political persecution.” This included information gathered from the emails about Palestinians’ sexual orientations, infidelities, money problems, family medical conditions and other private matters to coerce people into becoming collaborators or to create divisions in their society.

Another issue few Americans are aware of is the NSA’s secret email metadata collection program that took place for a decade or so until it ended several years ago. Every time an American sent or received an email, a record was secretly kept by the NSA, just as the agency continues to do with the telephone metadata program. Though the email program ended, all that private information is still stored at the NSA, with no end in sight.

With NSA fatigue setting in, and the American public unaware of many of the agency’s long list of abuses, it is little wonder that only slightly more than half the public is concerned about losing their privacy. For that reason, I agree with Frederick A. O. Schwartz Jr., the former chief counsel of the Church Committee, which conducted a yearlong probe into intelligence abuses in the mid-1970s, that we need a similarly thorough, hard-hitting investigation today.

“Now it is time for a new committee to examine our secret government closely again,” he wrote in a recent Nation magazine article, “particularly for its actions in the post‑9/11 period.”

Until the public fully grasps and understands how far over the line the NSA has gone in the past — legally, morally and ethically — there should be no renewal or continuation of NSA’s telephone metadata program in the future.